By John Walmsley and Lynn Crowe

(in Volume 27)

Introduction

Over the last 5 years or so Smartphones have become endemic in daily life. OFCOM (2015) [i]report that ownership in the 16-24 age group, the generation who have never known a world without the internet, has reached the 90% level. Ownership in older age groups continues to grow, with the 55-64 group now having just passed the 50% ownership threshold. OFCOM also record the remarkable statistics that smartphone use averaged across all adults is now 126 minutes per day, of which just over half is internet-related use (surfing, social media, apps, messaging). Perhaps this explains why it is almost impossible to walk the length of a typical high street without taking avoiding action from those coming the other way with eyes glued to their screens.

With this as the background it seems self-evident that at least some visitors to the countryside will want to use their must-have technology to enhance their trip. It is definitely not for everyone though, as some research shows (Walmsley 2014)[ii]. However a plethora of Apps is available for those who want them, and the functionality is highly varied: maps and navigation, recommended walks and rides, landscape recognition, historical and natural heritage, interpretive information, and sporting/exercise performance measurement.

Some of these Apps have been well used and highly successful, others have barely attracted any attention at all. To an extent, success will depend upon the size of the client market (e.g. lots of cyclists use Strava), and the inherent demand that exists for a particular type of digital information (e.g. maps and navigation via Viewranger). But putting simple supply and demand on one side, what are the fundamentals that make it possible for an App to deliver a compelling user experience and, conversely, what will put people off from using their Smartphones in their trips to the natural environment? A branch of Social Psychology called Technology Acceptance Theory helps to understand from where the answers to these questions may come.

Technology Acceptance Theory

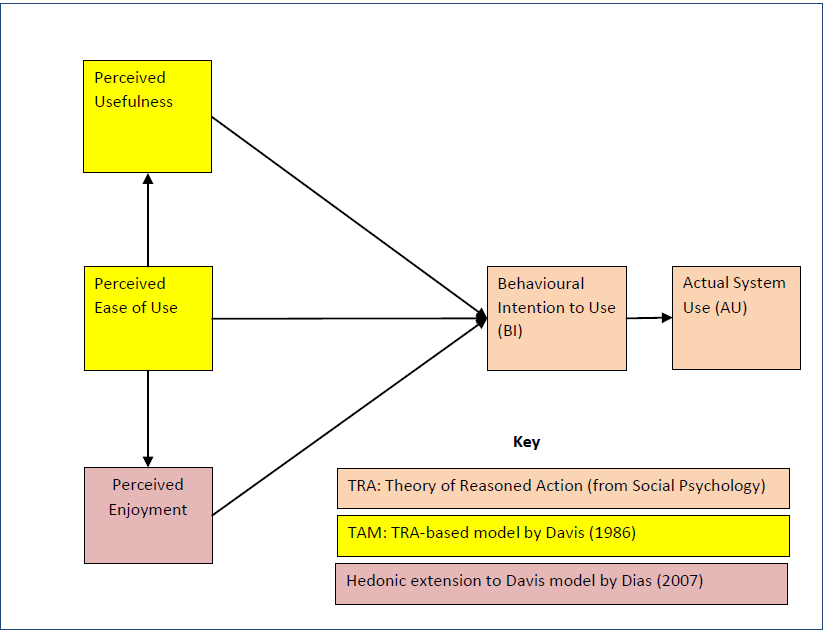

Behavioural models based on the work of Davis (1986)[iii] have become very successful in studying the way in which technology succeeds or fails to achieve widespread use. These models point to Perceived Usefulness and Perceived Ease of Use as being paramount determinants of the attitude of users to new technology, and thus their take-up at work or in the home. For a voluntary activity such as outdoor recreation, there is none of the compulsion to use mobile technology as might be the case of the work place, and it is therefore not surprising that Enjoyment (or lack of it) then also shapes users attitudes to use. This leads to models like Figure 1 which comes from a study of using mobile devices for contextual information in two European National Parks.

Figure 1 – Technology Acceptance Model (Dias 2007)[iv]

This model was used by participants in a workshop (ORN 2016) [v]to evaluate two outdoor recreation apps, to see if it helped highlight attributes that helped or hindered use by recreational users of the countryside.

ORN Workshop

Two very different Apps were used in the workshop to try out the model.

- East Sussex Walks, a native app commissioned by East Sussex Council to encourage people to walk a set of high quality circular routes (Figure 2). Navigation is GPS enabled, and there is also text and picture guidance. Native apps have to be downloaded and installed on a smartphone prior to use so, realistically, usage has to be pre-planned by the recreationalist.

- Thatcham Nature Discovery walking trails, created for the Berkshire Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire Wildlife Trust. Here the purpose was to deliver interpretive material to walkers concerning flora, fauna, conservation and heritage, on two walking trails starting and finishing at the visitor centre (Figure 3). This is a web app, which only needs a web browser and a means of recognising a web address (e.g. Quick Response (QR) codes or Near Field Communications (NFC)), in order to work. As these items are normally pre-installed on smartphones, usage can be opportunistic, but the user experience is completely dependent on good quality mobile coverage.

Figure 2 – East Sussex Walks (Google Play Store)

Both apps can be sampled by readers of this article, without actually having to come to either Sussex or Thatcham. The East Sussex app can be downloaded from the App/Play Store for iPhones and Android phones. The Thatcham app will need a QR code reader if the reader does not already have one. Those without a smartphone at all can use a PC or laptop to click in the links given in Figure 4 to see how it looks on an online smartphone simulator.

Figure 4 – Sample locations from Thatcham Trails (BBOWT)

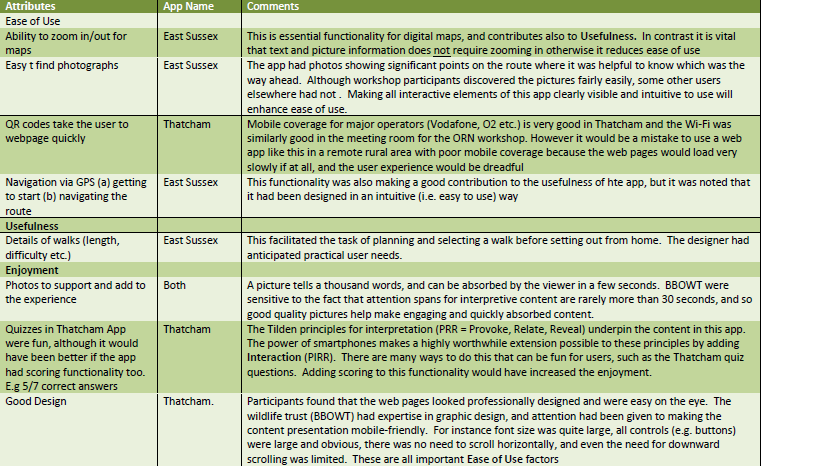

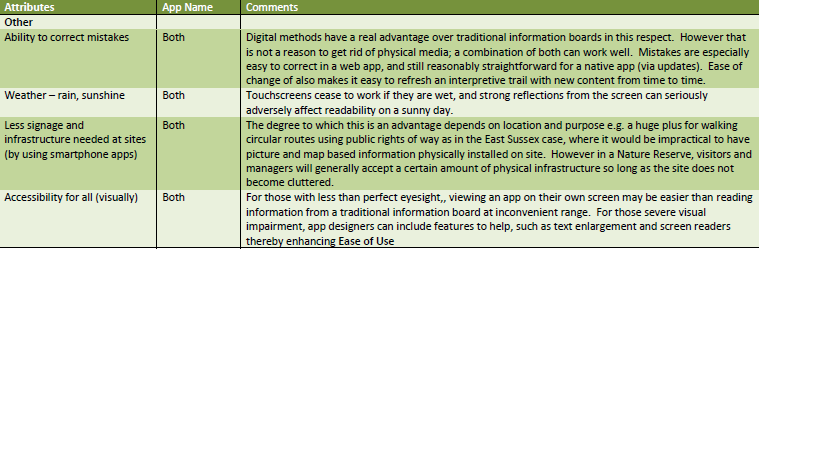

One thing that the authors were especially interested to discover, was whether participants in the workshop would find their opinions about the apps would fit neatly into the model or not. It was felt in advance that if there were too many points that were classified as “other”, that the model might not have passed the ORN test despite its credentials elsewhere. In Figure 5 below the Factors, and their attribution to the Dias model, were suggested by the participants. The Comments are those of the authors of this article, based on the research done at Sheffield Hallam University and practical experience from the Thatcham project.

Figure 5 – ORN workshop results

Conclusions

Most of the inputs from participants fitted into the model structure quite well. Of those that were classified as “other”, the weather issues are actually significant Ease of Use factors. The effects of both bright sun and rain are difficult to mitigate with current smartphones, although things will improve as display technology evolves in the future.

To add to the workshop results, there are other factors that the SHU research identified as being critically important for the success of an outdoor recreation app. Of these, two in particular seem to go beyond the considerations of Technology Acceptance Theory, and can each be represented by a catchphrase:

- “Content is king” sums up the need for information content to be delivered and presented in an engaging way. In particular, producing good interpretive material is surprisingly difficult, and is a skill that is in short supply.

- “Location, location, location” is normally an estate agent’s mantra, but it also encapsulates what an outdoor recreation app should be providing. Information has to be relevant to the location of the user, something that she can see and experience for herself. It should support the bond between the human and the natural environment, and give a sense of place.

In summary, the workshop elicited a wide variety of perspectives from participants, the technology acceptance model stood up to the “ORN test” reasonably well, and is useful tool for those considering applying smartphone technology to outdoor recreation.

[i] OFCOM (2015). The Communications Market Report 2015. Published 6/8/15 by the UK Government Office of Communications and last accessed 29/4/16 at: http://stakeholders.ofcom.org.uk/binaries/research/cmr/cmr15/CMR_UK_2015.pdf

[ii] Walmsley (2015). A Critical Evaluation Of The Application Of Mobile Information And Communications Technology To Countryside Access, MSc Dissertation, Sheffield Hallam University

[iii] Davis, F. D. (1986). A technology acceptance model for empirically testing new end-user information systems: Theory and results. Doctoral dissertation, Sloan School of Management, Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

[iv] Dias, E. S. (2007). The Added Value Of Contextual Information In Natural Areas. PhD thesis, Amsterdam, Vrije Universiteit (ISBN: 978-90-8659-173-2). Last accessed 10/5/14 at: http://www.feweb.vu.nl/gis/research/LUCAS/publications/docs/ESDias_PhD_web.pdf

[v] ORN (2016). 2016 ORN Research Seminar – Digital Data and Outdoor Recreation:

research, tools and applications. Outdoor Recreation Network at: https://www.outdoorrecreation.org.uk/events/