By Helen Baczkowska, Conservation Officer, Norfolk Wildlife Trust

(in Volume 29)

My earliest encounters with wildlife were on the few hectares of common land I now live beside and hold rights on. It was here I first saw a drifting barn owl, a grass snake swimming in a pond and taught myself the names of the wild plants that I found. Small wonder perhaps that I became an ecologist and developed a fascination with common land.

My role at Norfolk Wildlife Trust (NWT) involves working with the owners of the county’s Local Wildlife Sites (LWS), surveying flora and supporting the owners with wildlife management. These sites are registered for their value for biodiversity at a county level, sitting alongside National Nature Reserves and Sites of Special Scientific Interest as the best wildlife areas in a county; however, LWS is not a statutory designation. In Norfolk, 75 of over 1300 Local Wildlife Sites are registered common and a further 50 are fragments of former common land that are unregistered, but remain as ‘poors land’. Often retaining the name ‘common’, poors lands are fragments of larger commons enclosed in the  Eighteenth Century and frequently still resemble registered common land, being unenclosed semi-natural habitats with open access1. Poors land is managed by local charities set up at the time of enclosure to lease rights for firewood or raise money for the parish poor; this structure has often prevented ploughing, enclosure or development on these lands.

Eighteenth Century and frequently still resemble registered common land, being unenclosed semi-natural habitats with open access1. Poors land is managed by local charities set up at the time of enclosure to lease rights for firewood or raise money for the parish poor; this structure has often prevented ploughing, enclosure or development on these lands.

In April 2018, Norfolk Wildlife Trust, working in partnership with Norfolk County Council and University of East Anglia, launched Wildlife in Common, a two-year project funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund, with additional support from Essex & Suffolk Water. This unique, multi-layered project centres on the largely unrecognised role Norfolk’s commons play at the heart of many communities. Commons are places, often close to their homes, where people walk, seek solace or solitude and enjoy encounters with wildlife.

Evidence in support of this includes research I carried out in just one parish in South Norfolk, which showed that 5 commons close to a large village were the most popular places for walking with children or dogs2. Feeling close to nature or encountering wild species was an important part of people’s enjoyment of these places and the wildlife experiences did not have to be with rare flora or fauna; seeing wild flowers, hearing bird song and glimpsing muntjac deer were all considering enriching experiences. These findings reflect a mounting body of research into the importance of green spaces and everyday encounters with wildlife for physical and mental wellbeing3 & 4.

Over the next two years, Wildlife in Common will deliver targets on four main strands: working with volunteers to collect wildlife records on local commons, exploring the heritage of Norfolk’s commons, promoting the value of common land to communities today and finally exploring the potential for new commons to be created. I will look at each of these in turn.

Wildlife records are key to understanding biodiversity and the first major strand of Wildlife in Common will be to support local volunteers recording species and habitats on at least 60 commons or poors trust land across Norfolk. Support will take the form of training, skilled mentors and regular opportunities

to meet up and share experiences. The records generated will give us a greater understanding of the value of Norfolk’s commons for biodiversity, help us produce management plans for some commons and work with landowners or rights holders to deliver management on a number of key sites.

My work on Norfolk commons already has revealed that they support number of priority habitats, including valley fen, lowland heath, woodland and neutral grassland. Common land is found throughout the County, but with notable concentrations in the ancient landscapes of South Norfolk, parts of North Norfolk and on the edge of The Fens, as well as on the outskirts of some of the County’s market towns5. From a national perspective, these commons are rather small in size: a survey of common land carried out in 19976 shows the mean area of common land in Norfolk as 12.8 ha. In contrast, North Yorkshire and Cumbria have a mean common land area of 141.8 ha and 179 ha respectively. However, These lowland commons frequently have an intrinsic value for wildlife and play an important role in augmenting the statutory sites, helping to create a larger area available for wildlife across the county and providing ‘stepping stones’ for wildlife to move through a landscape.

Over the past decade, biodiversity conservation in the UK has embraced a landscape scale approach, with the dual aims of increasing the area available for species and allowing them to move in response to stimuli such as climate change. Central tools for delivering this are increasing the size of existing sites of wildlife interest and linking them by habitat restoration or creation across a landscape. The Wildlife Trusts across the UK have developed this work in a number of ‘Living Landscapes’, where delivery of landscape-scale conservation is focussed on key areas, often around clusters of existing nature reserves7&8.

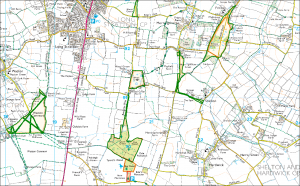

Habitats on common land can be a critical element in a Living Landscape and records collected through Wildlife in Common will allow NWT to gauge the extent of this value. Some of this work will concentrate on the South Norfolk Claylands Living Landscape; this is an unusual Living Landscape area as unlike most others it does not centre around a significant Wildlife Trust nature reserve, but instead focuses on an ancient landscape, enclosed in the Fifteenth Century after a catastrophic population decline during the Black Death9; common land often survived this enclosure where it was agriculturally marginal or crucial to the economy of the village. Consequently, a high number of small, often interconnected grassland commons remain, augmented by tall hedges, ancient woodlands and river valley fens. This intimate landscape supports species that rely on a varied countryside, including conservation priority species such as barbastelle bat, turtle dove and great crested newt10.

this is an unusual Living Landscape area as unlike most others it does not centre around a significant Wildlife Trust nature reserve, but instead focuses on an ancient landscape, enclosed in the Fifteenth Century after a catastrophic population decline during the Black Death9; common land often survived this enclosure where it was agriculturally marginal or crucial to the economy of the village. Consequently, a high number of small, often interconnected grassland commons remain, augmented by tall hedges, ancient woodlands and river valley fens. This intimate landscape supports species that rely on a varied countryside, including conservation priority species such as barbastelle bat, turtle dove and great crested newt10.

The second strand of Wildlife in Common focuses on the heritage of commons and will involve collaboration with both the Landscape History Unit at the University of East Anglia and the Norfolk Archive at Norfolk County Council. Norfolk’s commons hold a wealth of archaeological interest, from Mesolithic flint tool scatters and Bronze Age burial mounds to wartime practice trenches and pill boxes11. However some elements, such as Medieval boundary ditches, are often unrecorded and the history of use and enclosure largely under-researched. Wildlife in Common will provide people with the tools and materials to research the history of local commons, including changes of land use in the late Twentieth Century, when the agricultural use of the commons declined.

This strand links neatly to the third, which aims to instil pride in and awareness of Norfolk’s commons, as well as a wider understanding of what common land is. The will reach beyond the volunteers involved in the project and will embrace working with schools, artists and the local rural life museum.

The final element of the Wildlife in Common project will be to investigate the potential for establishing new areas of common land; this could be new public space provision within new developments, or looking at the outcomes of registering existing public space, such as the poors lands mentioned at the beginning of this article. If common land offers the range of public benefits outlined above, then considering the potential for new commons seems to hold some logic and has been under consideration by both academics and Natural England for some years12. The creation of new commons since the Registration of Commons Act 1965 has been limited, with one of the very few being in South Norfolk; St Clement’s Common in the village of Rushall was registered in the late 1990s by the then owner, who wanted the land left to the parish as a public amenity and considered commons registration the most effective method of protection. In the case of St Clements Common, registration rested on the granting of a right of estovers (collection of small or fallen wood for fuel) by the landowner to a local resident16. St Clement’s still remains at the heart of the parish, being used for walking and for local events; care of the site rests with the parish council, who have drawn on Norfolk Wildlife Trust for help and advice over the past decade, notably when a balance needs to be struck between managing wildlife habitats and maintaining the common as a public amenity13.

New commons could offer public space that both reflects the ancient landscape found in Norfolk and creates new or enhanced wildlife habitats; the granting of new rights of common could give local residents a stake in the land they walk on and enjoy. Perhaps the most interesting question here is what could new rights of common, relevant for the Twenty-First Century, consist of? Suggestions so far include community orchards, forest gardens or areas for foraging, hazel coppice for sustainable poles for gardeners and hay cutting for small pets.

My lifetime of living and working among commons has shown me that these are places that many people hold dear to their hearts, whether it is as walkers, wildlife enthusiasts, right holders or any number of interests that people have invested in land they do not own, but feel deeply connected to. Wildlife in Common will give a strong framework for promoting and understanding common land in a lowland county where common land is often taken for granted and not fully understood and hopefully also provides an opportunity for considering the role common land plays now and could play in the future.

References

- The Legacy of Norfolk’s Poors Land History, Norfolk Rural Community Council, available on line at https://www.historypin.org/en/person/52690, last accessed 08/04/2018

- H Baczkowska, Long Stratton Access to Countryside & Open Spaces June 2017. Norfolk Wildlife Trust

- Green space, mental wellbeing and sustainable communities, Public Health England, available online, last accessed 07/03/2018 at https://publichealthmatters.blog.gov.uk/2016/11/09/green-space-mental-wellbeing-and-sustainable-communities/

- S Bell, M Westley, R Lovell, B Wheeler, Everyday green space and experienced well-being. In Geographies of Health and Wellbeing Research Group. Available online, last accessed 07/03/2018 at https://ghwrg.wordpress.com/2017/02/21/new-paper-everyday-green-space-and-experienced-well-being/

- Norfolk County Council, Register of Common Land in Norfolk, 1975

- J Aitchison, K Crowther, M Ashby, L Redgrave (2000), The Common Lands of England, A Biological Survey. Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions, Rural Surveys Research Unit, University of Wales, Aberystwyth

- The Wildlife Trusts, Landscape Scale Conservation. PDF available online, last accessed 07/03/2018 at http://www.wildlifetrusts.org/node/3661

- The Wildlife Trusts, What are Living Landscapes? PDF available online, last accessed 07/03/2018 at http://www.wildlifetrusts.org/living-landscape/our-vision

- Norfolk Wildlife Trust, Claylands Living Landscape Strategy, June 2015

- National Character Area Profile: 83 South Norfolk and High Suffolk Claylands (NE544), Natural England 2014. Available online, last accessed at 07/03/2018. http://publications.naturalengland.org.uk/publication/6106120561098752

- Norfolk Historic Environment Record, available on live at http://www.heritage.norfolk.gov.uk/, last accessed 08/04/2018

- Duncan Mackay, Principal Advisor, (Reconnecting People and Nature Team), Natural England New Commons, What, where and why. Inspiring new cultural traditions for new generations. Newcastle Common Land Conference 5 July 2013.

- Personal communication, Rushall parish council