By Geoff Wilson and Ken Taylor, Members of the Cumbria & Lakes Joint Local Access Forum.

(in Volume 29)

One third of the total area of England’s common land is in the county of Cumbria, so, when Secretary of State (SoS) consent began to be granted for areas of common to be fenced as part of habitat regeneration projects supported by public funding, the Cumbria and Lakes Joint Local Access Forum[i] (CALJLAF) began asking some questions regarding allowances to maintenance access points.

Sixteen percent of Cumbria’s land area (112,900 ha) and 28% of the Lake District National Park is registered common land; the largest area of common land at county level in England[ii]. While almost 50% of the county’s commons are less than 1 hectare, 41 have registered areas of more than 1000 hectares; and 180 are contiguous so that the area of individual tracts of common land is much larger than emerges from the official register[iii]. The commons remain an economically important asset for sheep farming and to a lesser extent shooting, and are one of Cumbria’s greatest resources for outdoor recreation.

Grazed open fells are a characteristic feature of Cumbrian uplands in general and the Lake District National Park in particular, a factor which was key in gaining World Heritage Site listing by UNESCO (identified as Outstanding Universal Value 5[iv]). Over the last few years, members of the CALJLAF became increasingly concerned at the number of new fences being erected on Open Access Land (OAL) within the National Park. These were almost all associated with planting of successional scrub and (with a limited amount of new woodland[v]), where it was judged necessary to install ‘temporary’ fencing to protect growth from grazing animals (e.g. sheep, deer, rabbits) until the trees have reached a level of maturity that enables them to be self sustaining without protection. Creating ‘feathered’ edges and matching species to altitude helps to create a ‘natural’ effect to the new planting.

This openness, and the freedom of access that this affords, is highly valued by visitors; encroachment of fencing onto OAL is deceptive and cumulatively erodes this sense of openness. So, while the planting of scrub and woodland is desirable for reasons such as landscape, soil protection, biodiversity, water quality, carbon sequestration and flood management, these benefits have to be balanced against the possible negative effects on amenity, access and recreation, and in the Lakes damage to the Outstanding Universal Value. It is for this reason that mechanisms are in place under s38 of the Commons Act 2006 for the SoS (through the Planning Inspectorate) to be able to vet proposals for anything which will impede public access on common land, such as fencing, and to set time limits to their retention. The impact of the Environmental Impact Assessment (Agriculture) (England) (No.2) (Amendment) Regulations (2017)[vi] on fencing proposals are as yet unknown.

This openness, and the freedom of access that this affords, is highly valued by visitors; encroachment of fencing onto OAL is deceptive and cumulatively erodes this sense of openness. So, while the planting of scrub and woodland is desirable for reasons such as landscape, soil protection, biodiversity, water quality, carbon sequestration and flood management, these benefits have to be balanced against the possible negative effects on amenity, access and recreation, and in the Lakes damage to the Outstanding Universal Value. It is for this reason that mechanisms are in place under s38 of the Commons Act 2006 for the SoS (through the Planning Inspectorate) to be able to vet proposals for anything which will impede public access on common land, such as fencing, and to set time limits to their retention. The impact of the Environmental Impact Assessment (Agriculture) (England) (No.2) (Amendment) Regulations (2017)[vi] on fencing proposals are as yet unknown.

The incentive for landowners to plant scrub and woodland emerged from Environmental Stewardship, especially the Higher Level Stewardship strand[vii], and Woodland Creation Schemes[viii] administered by Natural England (NE) and Forestry Commission England (FCE) respectively. Both have been integrated into the Countryside Stewardship programme. Although the length of time over which consent for fencing on common land granted by the SoS is stated in the approval decisions, the terms of grant make no requirement for the fencing to be mapped and, because the term of grant and the term of SoS consent are not co-terminus, it has not proved possible to include a financial provision for removal of the fencing at the end of the authorised term. However, a number of agreement holders have undertaken to put money aside from their annual payments to cover the cost of fence removal at consent expiry[ix]. However, this is not always the case; and in some instances the initial grant terms have been insufficient to provide for all the access points which consultees have sought[x].

Background

The Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 (CROW Act) normally gives a public right of access to registered common land; which together with other areas of mountain, moor, heath and down are OAL. Additionally some large areas of Cumbria had been granted public access for open-air recreation arising from Part 1 of the Commons Act 1899 and s193 of the Law of Property Act 1925: now commonly known as Section 15 Access in reference to s15 of the CROW Act 2000.

Consequently, it is not surprising that the increase in s38 applications for fencing on common land[xi] and the availability of grants for tree planting and scrub habitat creation without mapping or removal requirements, gave some concern to the CALJLAF[xii].

Contact with other Forums indicated that the same issue was arising in parts of Yorkshire, the Peak District and Dartmoor … but to a much lesser degree than in Cumbria.

CALJLAF’s concerns are:

- the alignment of the fences being determined by factors which may not have sufficient regard for public access considerations;

- where consent is being granted for a ‘temporary’ fence, it is with a time limit of 10 to 15 years (usually towards the longer end of this range) but the terms under which grants are awarded and administered do not include provisions for the eventual removal;

- the attraction of some fencing for managing and marshalling stock, and previous experience with ‘temporary’ fencing used to assist re-hefting of flocks after the Foot and Mouth Disease epidemic in Cumbria in 2001, shows there is a significant risk that the expiry of the approval for a temporary fence is quietly forgotten and the fencing would become permanent fixtures permanent or be allowed to deteriorate to a point where they are unsightly and a trip hazard to walkers;

- With a recording mechanism in place, those responsible for removing fencing will be made more aware of their responsibility and, aware that the fence’s existence is being monitored, be more likely to fulfil their obligations to remove it when approval expires;

– There appears to be no plans within Defra, NE and FCE to ‘police’ these fence approvals when they expire.

- Although the position of public rights of way across planted areas is usually respected, the requirement to seek statutory authority[xiii] to insert gates may not be.

Representation made by the LAF in Cumbria

Most applications to erect fences have been prompted by a desire to secure grant under appropriate schemes at the time. Current applications can be made under Countryside Stewardship from 2015.

The current scheme, Countryside Stewardship (CS), is jointly delivered by NE, FCE and the Rural Payments Agency on behalf of Defra, and provides financial incentives for land managers to introduce environmentally-friendly measures for: conserving and restoring wildlife habitats, managi ng flood risk, creating and managing woodland and scrub, reducing water pollution from agriculture, each of which may involve fencing.

ng flood risk, creating and managing woodland and scrub, reducing water pollution from agriculture, each of which may involve fencing.

Approved schemes are generally developed with close co-operation between the delivery agencies and the applicants, which for common land is usually a commoners association and landowner.

Since 2008, the CALJLAF, as with many LAFs in their own areas, has been invited to give advice on design for a large number of schemes in Cumbria involving fencing. As a consequence, the more recently implemented schemes have are generally as ‘access-friendly’ as they can be.

In responding to consultations, the Forum has advised that various texts be employed in scheme agreements to ensure that the fence and all associated materials are removed after the specified time. The CALJLAF is not sure that it has succeeded to any great extent in this. Where permanent fencing is sought to facilitate Continuous Cover Forestry[xiv], and to avoid clear-felling, applications have to make that clear.

Where applications have been made by the National Trust or United Utilities (a major land-owner in Cumbria for water supply), CALJLAF has advised that the responsibility for removal of fencing etc. should be with the applicants and their successors. For other applicants (including a commoners association), CALJLAF has advised that the applicant be required to add the details of the fence removal into property deeds, binding them and any future owners.

More recent (July 2017) recognition of the impact of fences on the high fells of the Lake District has emerged from the area’s inscription as a World Heritage Site. Seeking a decrease in the permanent and redundant fences on the high fells has been adopted as some measure of the state of conservation of the Special Qualities and attributes of Outstanding Universal Value of the Lake District[xv].

Why mapping of fence location is needed

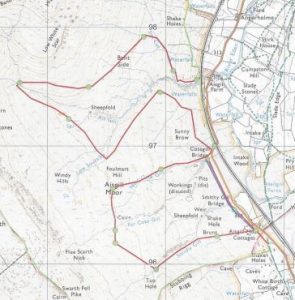

There is no publically available mechanism to track fencing or to ‘police’ its removal at the end of the term or when protection is no longer necessary. However, due to the speed with which the OS can now update digital mapping, ‘temporary’ fencing, which a mapping camera cannot differentiate from permanent boundary, is now featuring on OS mapping, with attached potential for user confusion. The fencing will be recorded in both duration and location on CS agreement maps, as well as for previous schemes, so the information is available.

The time period during which protection of trees and habitat is needed can be up to a generation in human time-scales. Without specific provision being made for the removal of ‘temporary’ fencing it is possible that unless instructed differently, future managers of the land in question will regard the fencing as being permanent and not be inclined to remove it to restore the openness of the area. Alternatively, the chances are that by the end of the consent period much of the fencing will have fallen into disrepair and will be littering the ground.

Because it is unlikely that government agencies will have the resources to police the removal of temporary fencing, the CALJLAF’s contention is that arrangements should be put in place to facilitate the general public and other interests to track the expiry of common land fencing approvals so that arrangements for removal may be followed-up. It is possible that CALJLAF itself could undertake this role.

The CALJLAF, in association with the Friends of the Lake District and others, has recommended that Defra and/or NE should provide the means for all temporary fencing on OAL, including common land, and all access points through temporary fencing, to be mapped in the same way that other exclusions and restriction to access on OAL is recorded. Also, that each map entry should be afforded a series of ‘attributes’ which details the date by which the fencing approval expires and who is responsible for its removal. Ideally and ultimately, this information could be made available on the MAGIC or NE OAL Exclusions and Restrictions website.

In response, the CALJLAF:

- has produced well received guidelines which are sent to anyone in the process of developing planting plans (and have made them available to Defra, NE and LAFs and officers in other authority areas;

- is developing a database (with support from NE, LDNPA and others) for recording the location and attributes of temporary fences on common land, which will serve as a prompt to pursue the removal of fences when the period of authorisation has expired;

- is maintaining contact with Defra/NE in response to an apparent reawakening of awareness of environmental issues at government level in the lead-up to Brexit.

[i] In 2017 The Lake District Local Access Forum and the Cumbria Local Access Forum merged into the Cumbria and Lakes Joint Local Access Forum, referred to here as CALJLAF.

[ii] http://www.cumbriacommoners.org.uk/common-landcom

[iii] http://www.cumbria.gov.uk/planning-environment/conservation/commons-registration-service/the-registers.asp

[iv] http://www.lakedistrict.gov.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/729755/4.0-Implementation,-Actions,-Monitoring,-Research.pdf

[v] What defines ‘woodland’ and what defines ‘scrub’ is a matter of continued debate.

[vi]… which means all fencing proposals of more than 2 kilometres of fencing within a National Park or AONB (4km outside) need an EIA assessment

[vii] See: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/environmental-stewardship-guidance-and-forms-for-existing-agreement-holders (visited 27th February 2018)

[viii] See https://www.forestry.gov.uk/ewgs (visited 27the February 2018)

[ix] http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160107131402/http://www.planningportal.gov.uk/uploads/pins/common_land/decision/com614_decision.pdf

[x] http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20160107132228/http://www.planningportal.gov.uk/uploads/pins/common_land/decision/com571_decision.pdf

[xi] Section 39(1)(c) of the Commons Act 2006 requires that in determining any application to carry out works on common the appropriate national authority shall have regard to the public interest, which includes the protection of public rights of access to any area of land.

[xii] Local Access Forums are regional bodies were established under the CROW Act 2000 and advise decision making organisations (such as local authorities) about making improvements to public access for outdoor recreation and sustainable travel. See https://www.gov.uk/guidance/local-access-forums-participate-in-decisions-on-public-access

[xiii] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/1980/66/section/147

[xiv] https://www.forestry.gov.uk/pdf/fcin29.pdf/$FILE/fcin29.pdf

[xv] http://www.lakedistrict.gov.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0008/729755/4.0-Implementation,-Actions,-Monitoring,-Research.pdf