By Jessica Allen

(in Volume 25)

Executive summary

Background

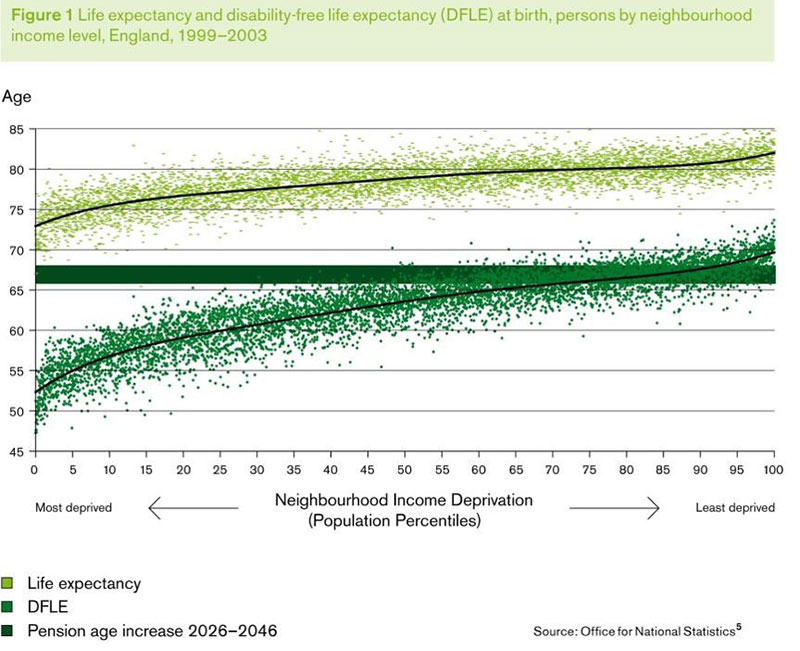

Health inequalities are the result of widespread and systematic social and economic inequalities. So close is the relationship between social and economic factors and health, that there is a clear social-class gradient in life expectancy and health outcomes. The relationship between neighbourhood income and health outcomes in England shows a relationship across the whole income spectrum so that everyone below the very wealthiest is likely to suffer from some degree of unnecessary health inequality, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Health inequality in England is estimated to cost up to £70 billion each year. Despite investment in addressing health inequalities, the health divide has continued to widen and the gradient to steepen.

Health and the natural environment are closely linked. Regular use of good quality natural environments improves health and well-being for everyone, including many who are suffering from ill-health. However, there are clear inequalities in access and use of natural environments. People living in the most deprived areas are 10 times less likely to live in the greenest areas. Indeed the most affluent 20% of wards in England have 5 times the amount of parks or general green space than the most deprived 10% of wards. So, people who live in the wealthier neighbourhoods are more likely to live in close proximity to good quality green spaces experiencing better health outcomes and living longer.

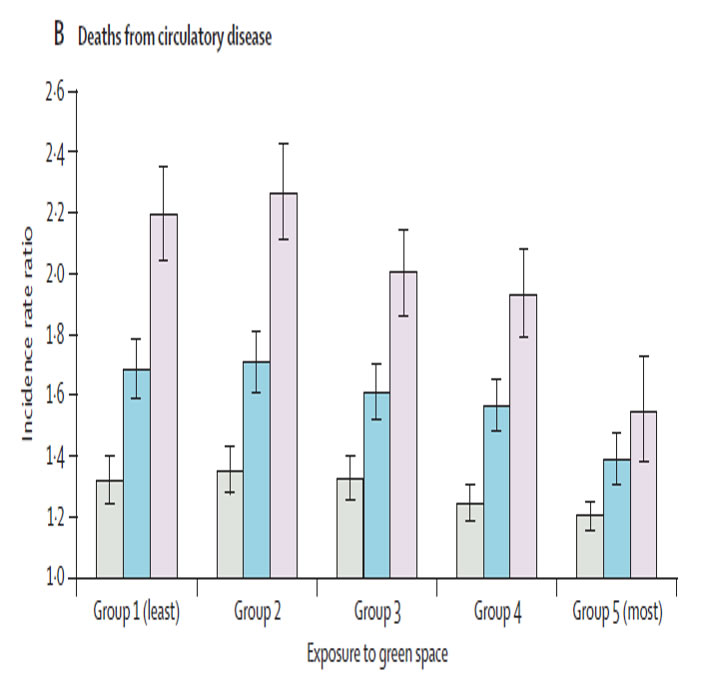

Overall better health is related to access to green space regardless of socioeconomic status and income-related inequality in health is moderated by exposure to green space. Research also demonstrates that disadvantaged people who live in areas with large amounts of green space may be more likely to use their local green spaces and be more physically active, thus experiencing better health outcomes than those of a similar level of disadvantage for whom such easy access to good quality green space is much less.

There is some research showing that interventions using the natural environment to improve health can deliver costs savings for health and related services and improve physical and mental health outcomes. So, increasing the amount and quality of green space can be part of a low cost package to address health inequalities, improve health outcomes and deliver other benefits.

The report sets out:

- The evidence on health inequalities and the contribution which the natural environment can make to improving health outcomes

- The challenges and priorities for practitioners, academics and policy makers from across the health and environment sectors, at both national and local levels, to better utilise the natural environment to help tackle health inequality.

- Recommendations for future, collaborative action by the health and

environment sectors

Evidence linking health and the natural environment is presented, with a specific focus on four priority areas:

- Tackling childhood obesity and physical (in)activity

- Improving quality of life when living with long term conditions

- Preventative solutions to premature mortality – preventing premature death from Cardiovascular Disease, diabetes, stroke for instance.

- Mental health including dementia

The four priorities for action are to:

1. Improve co-ordination and integration of delivery and ensure interventions are user-led

The cross-sector collaborations needed to achieve prioritisation of the natural environment to support delivery of health outcomes at both national and local levels are not working effectively, are often fragmented, and as a consequence resources can be wasted. Opportunities for aligning delivery and achieving win-wins through shared strategies between sectors are often missed. There is a need for far greater communication and collaboration between the natural environment and health sectors, which should also make it easier for the public to identify a coherent ‘offer’ around the natural environment.

The cross-sector collaborations needed to achieve prioritisation of the natural environment to support delivery of health outcomes at both national and local levels are not working effectively, are often fragmented, and as a consequence resources can be wasted. Opportunities for aligning delivery and achieving win-wins through shared strategies between sectors are often missed. There is a need for far greater communication and collaboration between the natural environment and health sectors, which should also make it easier for the public to identify a coherent ‘offer’ around the natural environment.

The move of public health responsibilities to local authorities and the establishment of Health and Well-Being Boards (HWBBs) and Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) should enable greater local collaborative action and commissioning. There is already Government commitment to strengthening the collaboration between Local Nature Partnerships and HWBBs. The natural environment sector could assist HWBBs and CCGs to fulfil their new duties in reducing health inequalities, improving health and wellbeing outcomes and meeting obligations under the Social Value Act.

Greater integration between the education and natural environment sectors is urgently required to help address health inequalities, tackle childhood obesity and improve children’s well-being and mental health. Building greater awareness and use of the natural environment into school learning practices is a powerful motivator for children and young people to be more physically active beyond more traditional sporting activities.

Poor quality facilities – or a lack of them – are often cited as reasons for not visiting natural environments. Creating a dialogue between the people who manage green spaces, local authorities and the community to establish what the public, particularly those not using green spaces, want from these spaces is an essential precursor to increasing greater use and improving access. Engaging communities is particularly necessary for socially excluded groups, who are at greater risk of poor health, have less access to, and use green spaces less.

2. Build a stronger evidence base to ensure programmes are evidence-led

The natural environment and health sectors need to work together to coordinate the production of high quality evidence that demonstrates the impact of the natural environment on health and health inequalities. While the environment sector has tested a wide range of innovative interventions, there is currently no standard for data collection and evaluation across the sector.

Comparisons of the efficacy of programmes are therefore difficult to make. Health commissioners generally require standardised information to inform the commissioning process. In order to demonstrate impact effectively, demonstrate relationships between the natural environment and health equity, and secure support from health commissioners, the evidence base requires improvement in a number of areas including:

- Collection of longitudinal and quantitative data

- Creation of standardised measures and assessments of interventions

- Greater use of physiological and biochemical indicators such as cortisol, EEG, blood pressure to engage with the health sciences

- Meta-synthesis across evaluation of interventions – both qualitative and Quantitative

3. Ensure sustainable delivery of services that use the natural environment

Efforts to reduce inequalities in health in a sustainable and cost-effective manner will be greatly enhanced if the natural environment sector can deliver on its potential as a low-cost solution to improving health outcomes across the socio-economic gradient.

Short-term funding measures rarely last long enough for projects to deliver any real impact, demonstrate sustainability, provide learning for development or enable collection of longitudinal data to establish impact and learning. Programmes should be designed and funded for the long term. Longer term programmes require funders, commissioners and organisations responsible for the design and implementation of programmes to think more strategically about the duration of projects and programmes, with a focus on ensuring sustainability of action. Funding is a perennial issue for the natural environment sector; without some further investment, the potential of the natural environment to improve health and reduce health inequalities will not be realised.

4. Increase the quality, quantity and use of natural environment spaces that benefit people’s health and help prevent ill health

In order to realise the potential of the natural environment to help reduce health inequalities and improve health, it is important to reduce systematic variation in the provision, quality and use of the natural environment and make the most of the health-giving aspects of using natural environments. Public Health England, Natural England and the Local Government Association are well placed to develop leadership locally and nationally and help prioritise the role of the natural environment in reducing health inequalities. Some of the levers, incentives and funding that are necessary to ensure that natural environments can support health equity can be developed through national leadership. For instance, clear policy ambitions for the provision of green space will help local governments and communities in addressing the limited provision of green space in some areas – a prerequisite for utilising green space to tackle health inequalities.

The potential benefits to health of greater, more effective and more equal use of the natural environment is clear; there is great opportunity.

Conclusions

Health inequalities in England are persistent and some measures show they are widening. The evidence presented in this report describes how increasing access to, and use of, good quality natural environments can help improve health and reduce inequalities; for example, how obesity, long-term conditions, illnesses which lead to premature mortality and mental health can be positively impacted by access to and use of natural.

Concerted action is required at national and local level. The new health system offers great potential for further integration of natural environment, health and education sectors including some potentially important policy levers, particularly the Social Value Act and Inequalities duties in the Health and Social Care Act 2012. Making the case for the benefits natural environments bring for health, education, reducing social isolation, and improving community cohesion for instance, will help to protect these valuable public assets. Public engagement is critical and this report has described some interesting and innovative ways of engaging and motivating people to use natural environments more.

In order to improve equity there must be a sustained and consistent focus and this means designing and delivering programmes for those who are least able or willing to visit natural environments. There are many excellent examples of programmes that do that; some are described in the report and these must be scaled up and combined with a focus on improving provision, quality and access for all. Approaches must be universal but also proportionate to need. Achieving sufficient funding, scale and longevity for natural environment programmes is difficult and all sectors involved have to work towards

providing evidence of impact and wide-ranging benefits for commissioners. Greater standardisation and coherence in methods of establishing impact across the natural environment should help and existing policy levers should be drawn on more, to provide a legal framework and support for commissioning interventions.

For more information see the detailed report… link