By Terry Robinson Chairman Outdoor Recreation Network and Chairman National Trust Minchinhampton and Rodborough Commons Committee Steve Kilmister Secretary Minchinhampton Commoners Council

(in Volume 29)

Minchinhampton and Rodborough Commons lie on the top of and along the steep slopes of two of the largest valleys that converge on the town of Stroud in Gloucestershire. Their plateaus and slopes, windy tops and shaded recesses are home to some of the highest quality calcareous grassland in Europe. The inferior oolite that forms their ground has yielded the highest quality limestone used, amongst other things to line the walls of the Palace of Westminster. And they provide fresh air, exercise and leisure opportunities for upwards from a quarter of a million people a year.

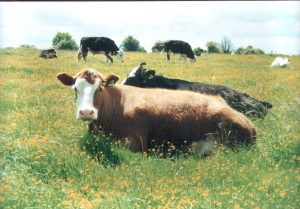

Yet, they are farmland, relied on by a handful of rights-holding graziers to provide summer grazing for beef cattle. The Commons remain important to the agricultural economy of the area. Grazing by cattle is an essential element of the management regime that has created the quality signified by every kind of ecological and archaeological designation with which they are emblazoned. But all is not well

Without grazing the Commons would revert to scrub and woodland. Weight gained may be greater on the home farmland but on the Common cows move around and select a wider variety of herbage giving extra flavor to the meat. Nevertheless, without additional support there probably would not be an economic case for putting cows out and managing the land for biodiversity. So, most of the graziers are in Higher Tier of the Countryside Stewardship schemes, which aims to maintain and enhance the calcareous grassland through grazing. The farms themselves are small so the Commons form a vital and traditional part of the way of farming has been practised in the area: it allows the home farmland to grow a crop of hay in the Summer.

While the graziers exercise their legal right to graze land that they do not own (the National Trust is the soil-owner), as is the case in all common land, the agricultural support regime is tailored to farming on enclosed fields and in more controlled conditions. Operating within the rules is much more tricky for those practising extensive grazing on common land.

all common land, the agricultural support regime is tailored to farming on enclosed fields and in more controlled conditions. Operating within the rules is much more tricky for those practising extensive grazing on common land.

Farms are worth a lot of money: it is a classic asset-rich, cash-poor business. The Graziers’ Committee has been in negotiation with the Government about the administration of the Single Farm Payment since 2005 and has had some success in establishing their case for a more supportive payment regime and examining feasible options. But graziers remain perplexed. Many of them are third or fourth generation graziers, using the common land primarily because that is the way the family has always farmed, present day incentives being a secondary consideration to a strong sense of tradition and sense of place.

One of the key challenges issue is that much of the biodiversity exists on the steeper scarp slopes and naturally the cattle will graze the flatter more accessible plateau. Maintenance of the quality of the commons on the slopes is often only possible by restrictive grazing, meaning that temporary fencing is needed to contain cattle in to a particular part of the common where scrub is developing through under-grazing. Maintenance of the fences and the welfare of the cattle needs intensive management by the farmers concerned. It is this level of intervention that the Countryside Stewardship agreement is supporting. It is not helped by bizarrely motivated vandals who destroy the fences.

The methods and regimes that graziers and their parents and forefathers adopted are largely responsible for the superb state the land is now in. Guidance from conservation agencies and funders is welcomed but can appear to be overly prescriptive about methods of vegetation management and animal husbandry that it risks choking the very existence of continued grazing. What all sides agree on is that without continued grazing, the superb biodiversity of the area, with its many rare plant and insect species, such a Duke of Burgundy butterfly, Adonis Blue butterfly and the Pasque Flower looks impossible to maintain.

Intense measurement and finely defined management regimes may be easier for farmers in enclosed and more controlled units but can be extremely difficult for graziers on common land. Uncertainty over the further changes that will follow after Britain leaves the European Union is a further perturbation.

One possible option currently being considered is to develop management regimes framed around results achieved rather than detailed method prescriptions, and on initial examination this sounds attractive. Readiness to discuss a broader range of options for dealing with topical problems, such a TB would be helpful as this is a significant factor for livestock farmers in Gloucestershire. For instance, sward management by burning was practised earlier in the twentieth century but is hard to raise as a discussion point now due to the level of legal protection for the rarer butterfly and plant species on the common.

One possible option currently being considered is to develop management regimes framed around results achieved rather than detailed method prescriptions, and on initial examination this sounds attractive. Readiness to discuss a broader range of options for dealing with topical problems, such a TB would be helpful as this is a significant factor for livestock farmers in Gloucestershire. For instance, sward management by burning was practised earlier in the twentieth century but is hard to raise as a discussion point now due to the level of legal protection for the rarer butterfly and plant species on the common.

The Commons lie in a well populated part of southern England. Both local people and those on longer journeys take the roads over the Commons.

The grazing season is from May 13th till end of October. During that time, cattle are roaming the Commons, as they have done for centuries, long before the motor car. They are not fenced from the roads so cross them frequently, stand in the highway and often use them for moving around the area. It is hard to make drivers understand the special care, patience and vigilance needed when sharing open country with bovines, who live up to their name, as far as road sense is concerned. Over recent years, the average annual count of cattle fatalities is 6, most of them from early September onwards as the light declines and traffic volumes increase. But the average is misleading: the range of fatalities has been as low as two and as high as a dozen.

Following several years campaigning by the graziers, the National Trust, and local councils a speed limit of 40 mph for all roads crossing the Commons was introduced in 2000. Police data shows that even those with good reactions cannot stop a car at night within the scope of their dipped headlights at any speed greater than 28mph. Most cattle are killed at dusk or at night so the 40 mph speed limit has to be lowered or an alternative approach to get the message across to the public such as outlined in the New Forest article in this edition.

In 2014, the local Road Safety Partnership convened a group of interested stakeholders, including local councils, the police the National Trust Advisory Committee, graziers and the highways authority to reduce the incidence of car crashes. Their work has seen the installation of better signage, speed monitoring technology and further work to educate local motorists via the media.

But there are policy issues that need rectifiying, too. Many cars use the Commons as a rat run to avoid a congested, sinuous A road along the valley: it also has a 40 mph speed limit. 80,000 vehicles cross the Commons on the spine road each week. A major contribution to the increase in traffic has been the installation of a new roundabout at one end of the Commons: its design induces traffic to leave the A road and take the unclassified road over the Commons. Monitoring speeds reveals that a substantial proportion of vehicles exceed the 40 mph limit, some spectacularly so.

Solutions discussed by the working group include speed humps on the spine road. Highways regulations ban such devices outside a 30 mph limit and where there is no street lighting. Hitting a cow at 40mph causes a lot more damage to a car and occupants than hitting a hump at the same speed. The partnership is moved to work with others looking after unfenced roads in other parts of England and Wales to persuade the Department of Transport to consider the special case of commons in respect of speed humps.

The Group has also examined average speed cameras but the capital investment and lack of practical track record has made this difficult. Streetlights on the Common have also been mentioned but would be aesthetically objectionable. Luminous collars for the grazing animals have been tried but none found usable.

At the back of all this discourse are real people. Most farmers feel their pulse rate go up every time the phone rings when the cattle are out, so upsetting is the travail of dealing with an injured animal. Drivers of vehicles, many of whom are divorced from the reality of what they are doing when driving along the unfenced roads are, nevertheless shattered when involved in an accident: their vehicle is also likely to be a write-off. Speed limits can never be set low enough to ensure an animal hit by a vehicle is unharmed. The solution has to be ensuring drivers take on the right frame of mind: a mindset that acknowledges that when the cattle are out, anything can happen. There is just some hope that a 30 mph speed limit would impress that realisation on drivers. So the group is pressing for one.

The Commons have always been a busy space, heavily used by people while harbouring very rich flora and fauna. A group including the National

Trust and the Stroud District Council, as the planning authority is examining the likely impact of 5,000 new dwellings planned for the Stroud area in the Local Plan. It is fair to assume this will generate more visitors to the Commons, some of which are Special Protection Areas, SSSI, Special Areas of Conservation and Local Nature Reserve.

The National Trust has commissioned the Stroud Valleys Partnership to conduct baseline surveys of the current condition of tracks and paths on the Commons and places where there is some erosion. Drone photography has been commissioned to accompany the survey. The images will be compared with aerial photographs taken in the last decade and with photographs from the 1950s. Monitoring of visitor numbers and visitor surveys will also be undertaken.

The group is working on a formula for a developer contribution attached to each house built within 3 km of Rodborough Common, (currently £200) that will generate funds to manage the impact of more people using the Commons for open air recreation. The negotiations are towards the National Trust receiving funds to spend on managing the commons and possibly establishing more open space and upgrading the management of other open spaces to relieve footfall pressure on the commons.

The title is Bislama, the local pidgin language in Santo, Vanuatu. The English translation is, “Cattle are good for the soil”