By Dr Andrew Humphries

(in Volume 29)

‘Unbounded freedom ruled the wandering scene

Nor fence of ownership crept in between

To hide the prospect of the following eye

Its only bondage was the circling sky…’

(John Clare, written 1812-1831)

John Clare represents the beauty of pre-enclosure landscape, in which the unenclosed common was a symbol of the freedom of ordinary people. The link between commons and access for outdoor re-creation remains critical to the future relevance of England’s upland commons.

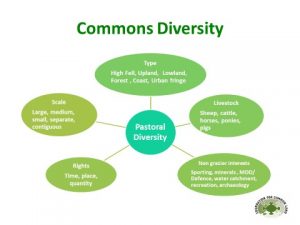

In 2005, Jim Knight the Minister for Rural Affairs, Landscape and Biodiversity whose oversaw the introduction of the Commons Act 2006 summarised the ‘relevance and role of common land to society as, central to our hill farming culture, our single most important wildlife resource, and open space’[1]. To that we may add many other values including water supply, heritage, carbon store and exceptional sense of place.

Commons and right of common

Commons emerged from prehistory when land was an open access resource and over time as populations developed acquired rights of ownership and use. All common land belongs to someone and has done from time immemorial, over which others have legal right of use. Since medieval times ownership has generally been vested in the Lord of the Manor or their legal descendant. Commoners’ use of the land has been exercised communally or in common. The range of rights is very diverse dependant on the resources of each. The most generally known is the right of common pasture or grazing. Others include the right to wood for fuel (estovers), turf for fuel or roofing, fish (piscary) and bracken for fuel and bedding or as a means of improving grazings.[2] Many battles were fought on common land which coincidentally may have protected crops in neighbouring enclosures. Marston Moor ((1644) and Sedgemoor (1685) are examples.

Whilst formal ‘de jure’ access for recreation on a very limited scale dates back several centuries the Countryside and Rights of Way Act 2000 gave the right of public access over all registered common land. Prior to this, on many upland commons open access was ‘de facto’ a long established practice reflecting a customary approach pragmatically adopted.

Custom and Customary Agrarian Practice in the Lake District.

Agro-pastoralism focussed around common grazings has developed and adapted from ‘time out of mind,’ by three strongly linked ‘pillars’: heafing[3], neighbourliness and custom. Custom in essence has been the glue that holds remarkable indigenous pastoral systems together.

‘For a custom taketh beginning and groweth to perfection in this manner. When a reasonable act once done is found to be good, and beneficial to the people, and agreeable to their nature and disposition, then they do use it and practise it again and again, as so by often alteration and multiplication of the act is becomes a custom, and being continued “time out of mind” it obtaineth the force of law’.[4]

(Carter, Lex Customaria 1696)

Custom was based on key principles, antiquity, continuance, certainty and reason. Custom is local, and has been expressed as custom of the manor. Since custom is not frozen in time but demonstrates continuity, it offered local communities the opportunity to express their diversity in developing husbandry in ways that seemed to work best for them, but with the capacity to update in response to changes in the natural and economic environment.

In the Viking period law and culture was focussed on assemblies or ‘things’ where matters of concern or ‘things that matter’ were discussed. Collingwood refers to the ‘shepherd s parliament’ at Thirlmere, and describes the ting mound in little Langdale as the ‘Lakeland Tynwald.’[5]

s parliament’ at Thirlmere, and describes the ting mound in little Langdale as the ‘Lakeland Tynwald.’[5]

After 1066, manorial practice reflected the Norman model and established Customary Baron Courts, a private jurisdiction and the property of the lord, to enforce the customs of the manor. The business was overseen generally by the lord’s steward and the business undertaken by a jury of tenants. Courts acted as a forum where members of the local community could obtain justice and meet to discuss matters of common concern which included the management and use of common land. They met ‘for lord and neighbourhood’. Acting as a communal memory they formed a bridge between legal theory and day to day farming practices.[6]

Customs were in practice contested through conflicting claims. That is how custom adapted to local needs, remaining relevant and useful with an ethos of consensus. The reality is that the courts were supported by informal negotiation on the ground where on occasion personal vendettas surfaced. Not everyone could be satisfied yet the system represented a sort of great collective bargain. Custom needs to be understood in the context of the past and present in order to secure a future based on the principles of local sustainable management.

In Cumbria and surrounding areas of northern England customary tenant-right developed as a particular form of land tenure linked to the obligation to provide military service on the Scottish border. In return, customary tenants enjoyed a high level security of tenure. The freedom to devise their farms allowed succession by family members in particular and prevented landlords from taking their estates in hand, leaving the landholdings in the hands of yeoman farmers and successive generations of family farms.

Family farms view ‘improvement’ differently to major landowners in respect of risk and investment. It is significant that Cumbria has more than 180 commons which are contiguous with others, presenting the open Lake District landscape which is at the very heart of its attraction and special value. Creating a network of walls would have been expensive to build and maintain. Sheep heafed on their customary areas on open fells, managed by skilled shepherds and gathered by trained dogs were able to reduce financial risk and shape inspirational landscapes with contrasting textures and colours with vernacular features that ‘grew naturally’ from the land. The system arguably derives much from custom, customary tenure and Customary Courts Baron, which has sustained a culture of purposeful animal husbandry consonant with high quality public goods.

Custom shaped the tenure and diverse commons management across and within England’s hills and uplands in diverse settings. Flocks of sheep, or a sufficient portion to sustain a heaf were, and are generally ‘tied to the hearthstone;’ that is they are appended to the land holding. At the commencement of a tenancy each party appoints viewers or representatives to agree a valuation of the landlords stock taking account of numbers, types of sheep and their condition. Incoming tenants were required to find two guarantors or bondsmen to accept responsibility to return the same number type and condition of sheep at the end of the tenancy with agreed compensatory terms for any shortfall. ‘Shepherds meets,’ twice yearly gatherings were famed for social intercourse with feasting and singing coincidental with the exchange of strays. Claimants of strays were required to recite their flock marks in public to ensure that ‘each was returned to his own’.

Flocks of sheep, or a sufficient portion to sustain a heaf were, and are generally ‘tied to the hearthstone;’ that is they are appended to the land holding. At the commencement of a tenancy each party appoints viewers or representatives to agree a valuation of the landlords stock taking account of numbers, types of sheep and their condition. Incoming tenants were required to find two guarantors or bondsmen to accept responsibility to return the same number type and condition of sheep at the end of the tenancy with agreed compensatory terms for any shortfall. ‘Shepherds meets,’ twice yearly gatherings were famed for social intercourse with feasting and singing coincidental with the exchange of strays. Claimants of strays were required to recite their flock marks in public to ensure that ‘each was returned to his own’.

With changes in the law and a decline in the formal manorial courts custom continued on a more informal basis. However since World War Two and particularly over the last four decades legislation has subsumed custom and created a governance which has transformed from bottom up to top down, a situation that needs to be integral to the radical changes in agricultural policy that is imminent.

Self Help

Through self-help, voluntary commoners associations have been formed over the past 20 years to support graziers to negotiate with government agencies concerning stewardship and other organisations to protect their collective interests. In this way commoners are actively working to make things better and at the same time provide a mechanisms for better communication between the commoners and outside organisations. In 2003, Cumbria Commoners formed a Federation as a regional representative voice supporting and protecting commoning. Guidance on good practice has been developed for adaptation and use by local commoners associations. The guidelines outline the approach to good practice, but are not prescriptive. Commoners can adopt and adapt, to suit the diverse needs of their own community and common grazing. Equally significant has been the formation of the Foundation for Common Land. Both organisations are innovative in making a difference, working to enable commoners to contribute fully to shaping the future of their families, neighbours, and other stakeholders.

The three pillars of heafing, neighbourliness and custom are central to the restoration and development of an indigenous culture. Heafing evolved from communal working, gradual change and stable numbers. The new paradigm has been about reducing numbers without consideration for stability, a growing interest in fences, and more interest in intensive shepherding. Custom which had the force of law and was locally devised and revised according to need is now largely replaced by statute and regulation which do not effectively aspire to locally devised changes which are dynamic, diverse and adjusted by experience.

Policies pay little attention go good neighbourhood as a priority, yet articulate the value of multiple stakeholder interests including outdoor recreation, over the same area of land. Good neighbourhood in the context of increasingly complex land management aims must be participatory and collaborative to minimise coercion and competition. Recreational activities have the potential to enhance enjoyment in harmony with common grazing, but as Ella Fitzgerald musically communicates, ‘taint what you do it’s the way that you do it’. ‘Ations’ are the outcome of suffixes added to words produce results. Education, communication, and collaboration are ‘ations’ that form the building blocks of harmony between users on commons.

Post –World War Two policies brought legislation to support agricultural production and conservation of natural resources but without linking the two. Thus the seeds of tension were sown. The answer seems clear but making it a reality demands understanding if wise decisions are to be made and reciprocity and respect between interested parties improved. Critically, public goods such as landscape, access, biodiversity, provision of water and food security cannot be delivered without socio economic aims that are founded on sound principles and practice, subjected to a wider understanding and mutuality that is expressed in wise decisions. Common graziers have depended on self-help for most of history which holds vital potential to revitalise a sense of purpose and establish renewed efforts to enable mutuality.

the two. Thus the seeds of tension were sown. The answer seems clear but making it a reality demands understanding if wise decisions are to be made and reciprocity and respect between interested parties improved. Critically, public goods such as landscape, access, biodiversity, provision of water and food security cannot be delivered without socio economic aims that are founded on sound principles and practice, subjected to a wider understanding and mutuality that is expressed in wise decisions. Common graziers have depended on self-help for most of history which holds vital potential to revitalise a sense of purpose and establish renewed efforts to enable mutuality.

Understanding provides the essence for valuing, on which mutuality depends. What people see and what they have in their heads are often different. Bridging that gap is a responsibility of all stakeholders who interact on the ground. Quiet individual recreational activities such a walking present few problems with the exception of dog control. Larger scale activities such as hang gliding may be potentially disruptive to grazing behaviour, gathering or the settling of ewes with young lambs on the common in early spring. Sometimes it ‘t’aint what you do but when you do it.’ With understanding, planning and discussion with the commoners the potential for reciprocity and respect is easier than it may seem.

Common graziers have depended on self-help for most of history which holds vital potential to revitalise a sense of purpose and establish renewed efforts to enable mutuality. Many commons have a voluntary association of graziers, some regions have an organisation representing a wider community of commoners and at a national level the Foundation for Common Land is a charity whose central aim is to sustain active commoning as a public good. These are important points of contact to help users to work to mutual benefit and many have websites with valuable educational material.

‘A peasant will stand for a long time on a hillside with his mouth open, before a roast duck flies in.’

(Chinese proverb)

[1] Fifth National Seminar on Common Land and Town and Village Greens. University of

Gloucestershire.

Web; www.glos.ac.uk/ccru

[2] Hoskins, W.G. & Stamp, D.L. The Common Lands of England and Wales, Collins, London, 1963, p.4

[3] Heafing is the adaptation of sheep to a particular part or heft of the common. This link is passed on from mother to lamb. Each flock has a heaf largely separate from its neighbours without the need for fences or walls.

[4] Thompson, E.P. Customs in Common, The New Press, New York, 1924, p.97

[5] The Vikings in Lakeland, Saga Book Vol. xxiii, Viking Society for Northern Research, University of London, 1990-1993.

[6] Winchester, A.J.L. The Harvest of the Hills, Edinburgh University Press, 2000, p.33

PASTORAL COMMONS LINKS

The Foundation for Common Land is a charity supporting active pastoral commoning as a public good i.e. not a sectoral campaigning organisation.

www.foundationforcommonland.org.uk

There are some good information leaflet and other material as well as current issues and opportunities.

The Federation of Cumbria Commoners and the Dartmoor Commoners Council are both regional bodies primarily supporting commoners, though in both cases working to benefit common graziers in ways that are consonant with wider stakeholder interests.

www.dartmoorcommonerscouncil.org.uk

Of the government agencies Natural England have material on their website on common land

Defra have information mainly at a policy level